“The findings in this book provide a cause for hope, as they show that there are already labour law experiments on local and national levels that have resulted in increased wages and better labour conditions for workers. Based on this, I suggest a bold international campaign to promote a global living wage and regulate work in supply chains.”

LIVING WAGE: Regulatory Solutions to Informal and Precarious Work in Global Supply Chains

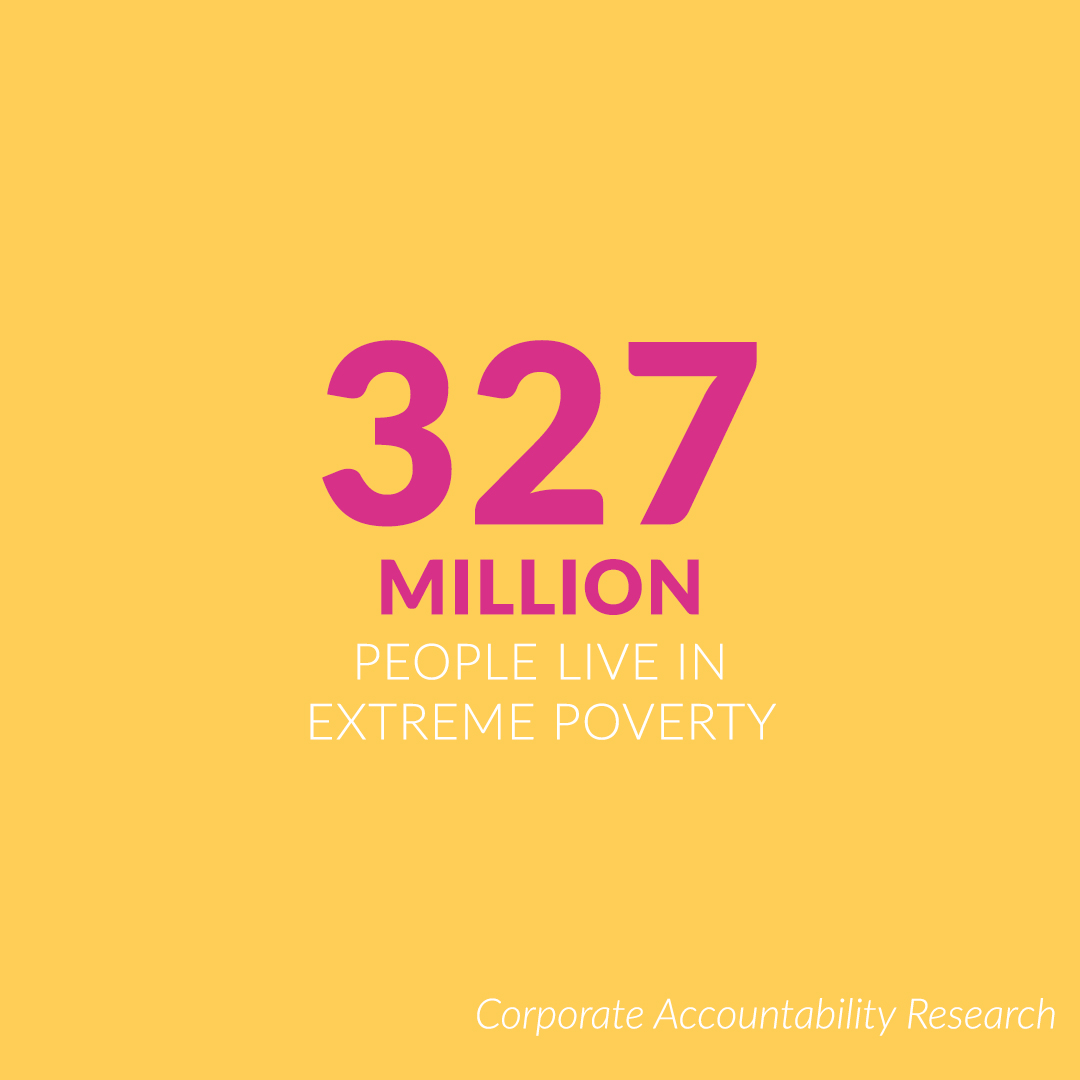

Dr Shelley Marshall has undertaken research in a range of countries, including Australia, Bulgaria, Thailand, and Cambodia, studying the working conditions of informal workers that often work for poverty wages. Her book, ‘Living Wage: Regulatory Solutions to Informal and Precarious Work in Global Supply Chains’, proposes strategies to improve and enforce minimum wages for workers that suffer the consequences of the constant pressure from powerful actors to cut production cost. At the heart of the proposal is the dire need for an international labour law. This is a bold proposal for addressing working poverty - one of the most pressing social justice issues of our time.

Find more resources here.

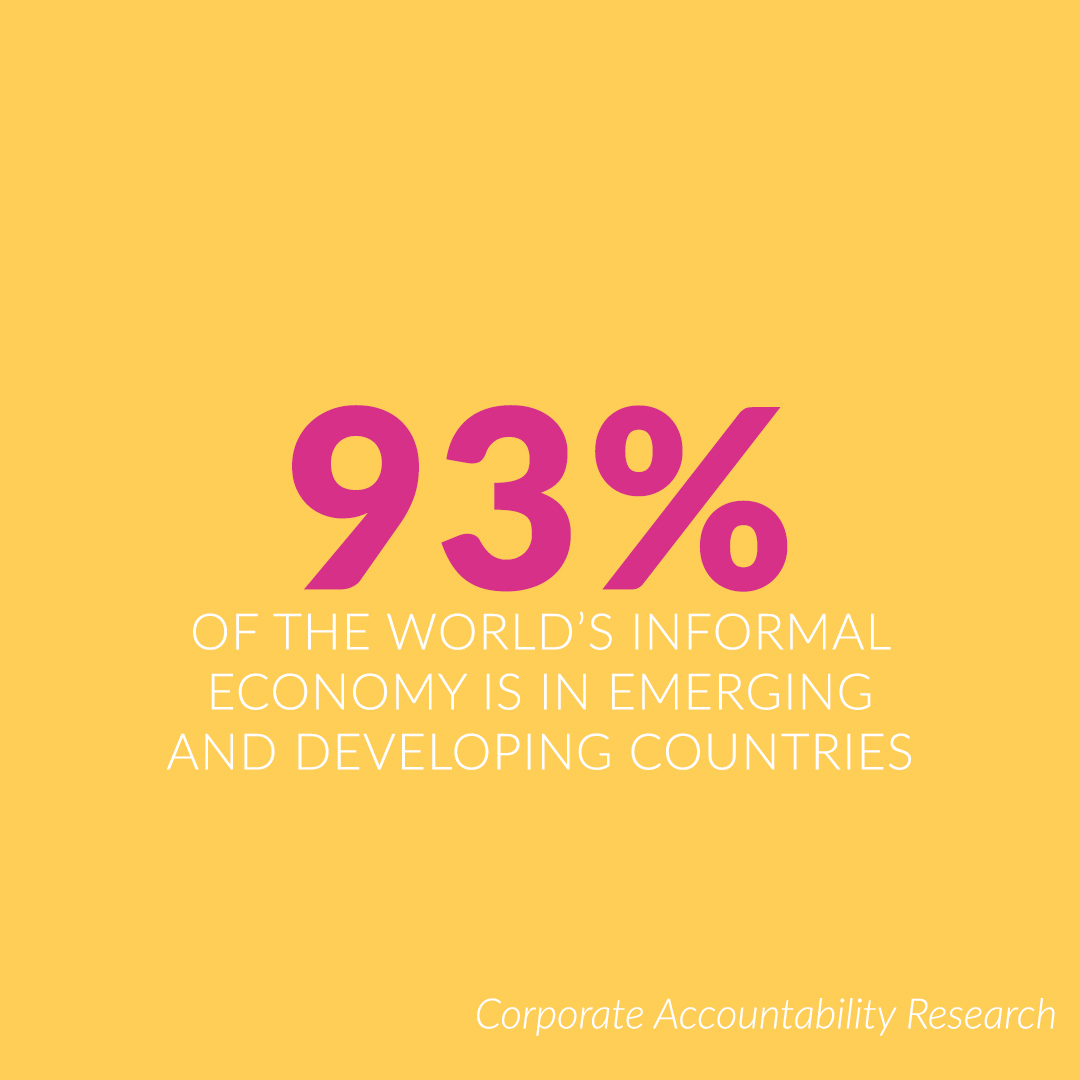

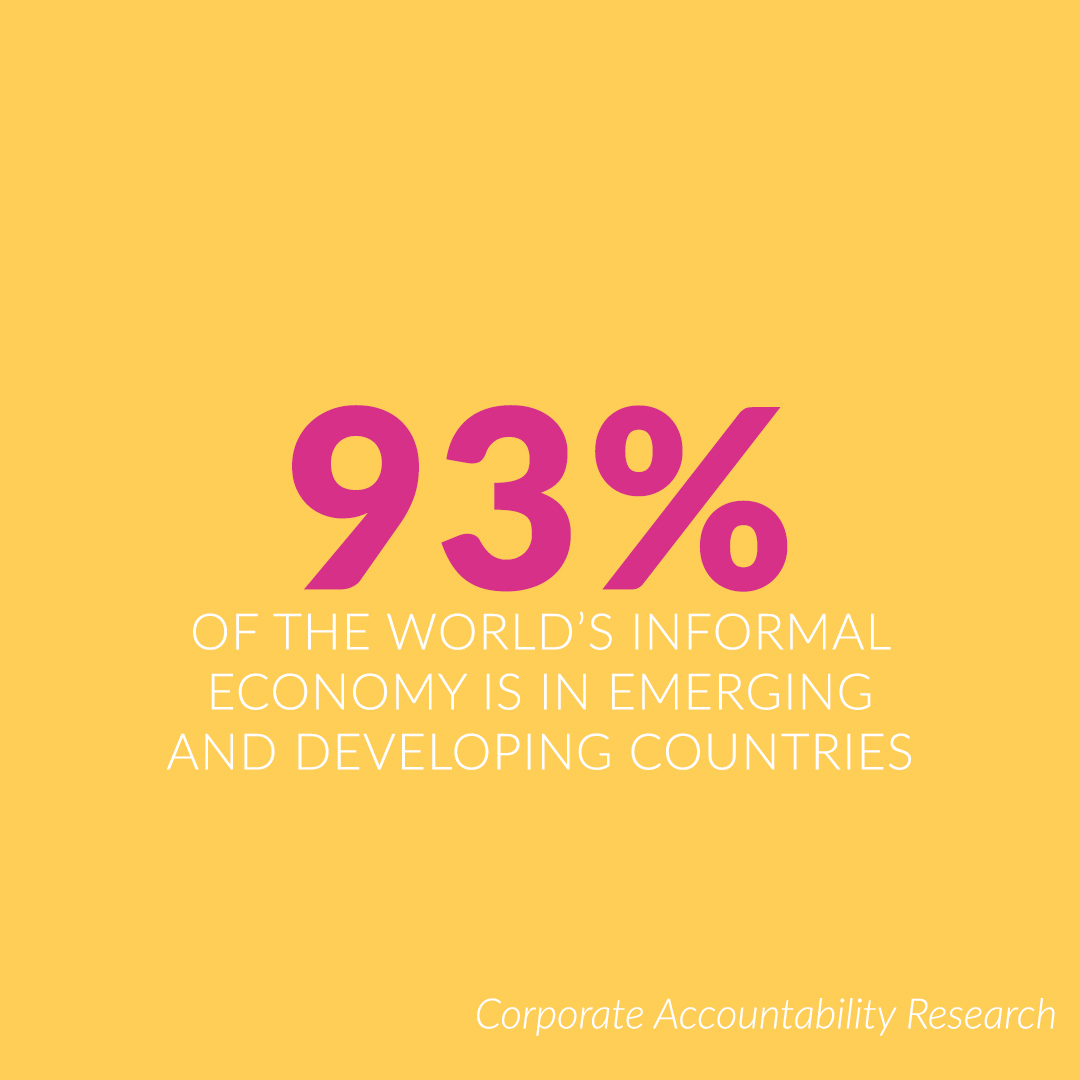

Although governments worldwide have committed to implementing minimum wages for years, many have yet to raise wages to a living wage rate and enforce them. The main reason for this is that it is very hard for single countries to do this, as they fear that corporations will move their production to other countries with cheaper production costs. To avoid this, we need a Global Living Wage Instrument so that countries can work together across regions and internationally to achieve a wage which allows people a decent life. Pivotal to this is that they are given a realistic timeline with incremental wage increases over multiple years.

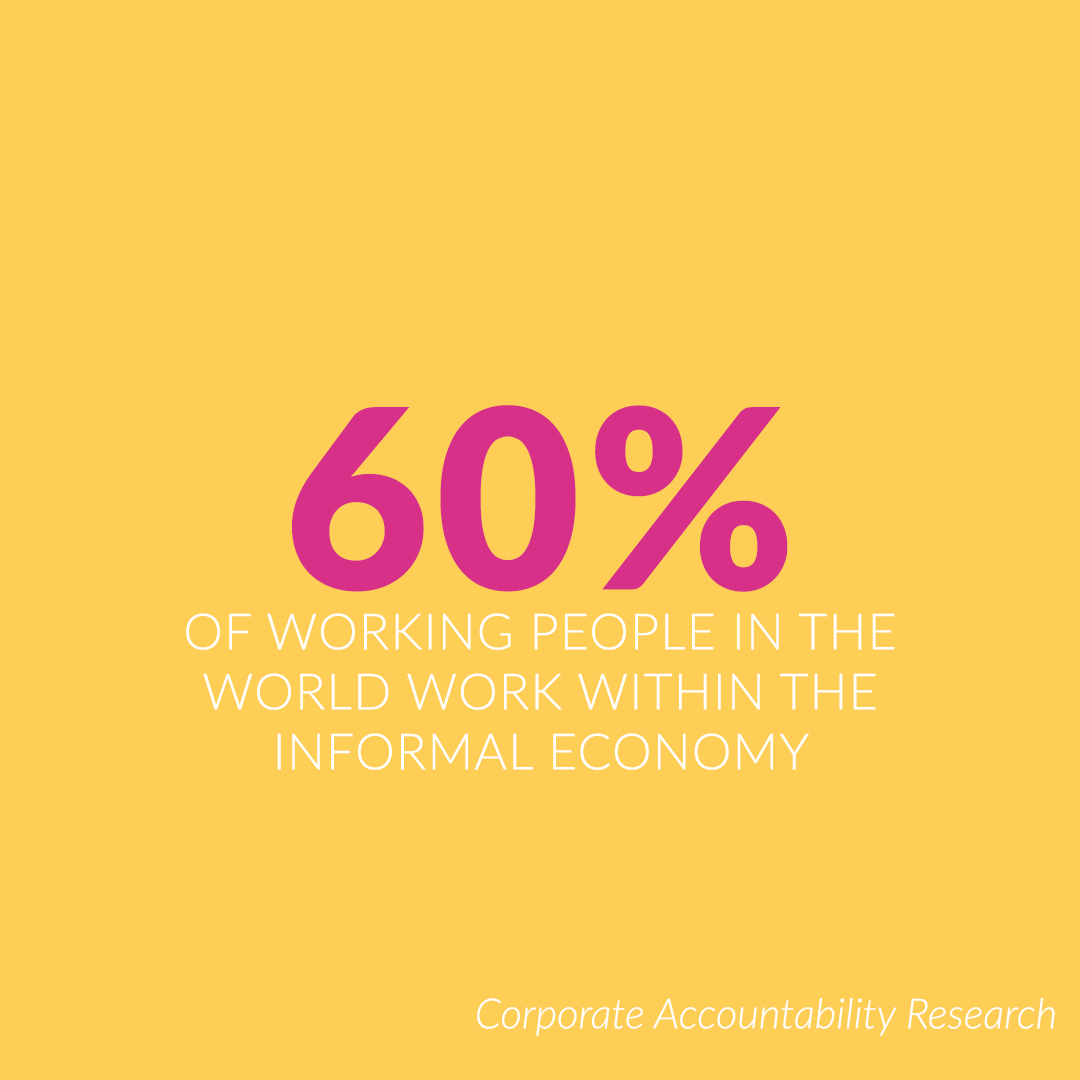

There is a need for a multi-level, transnational labour law to ensure a living wage for all because work today occurs in global supply chains where workers and capital cross borders, whereas labour laws do not. The global living wage strategy proposed in my new book is based upon extensive empirical research and regulatory theory and is more ambitious than previous real-life experiments and academic propositions.

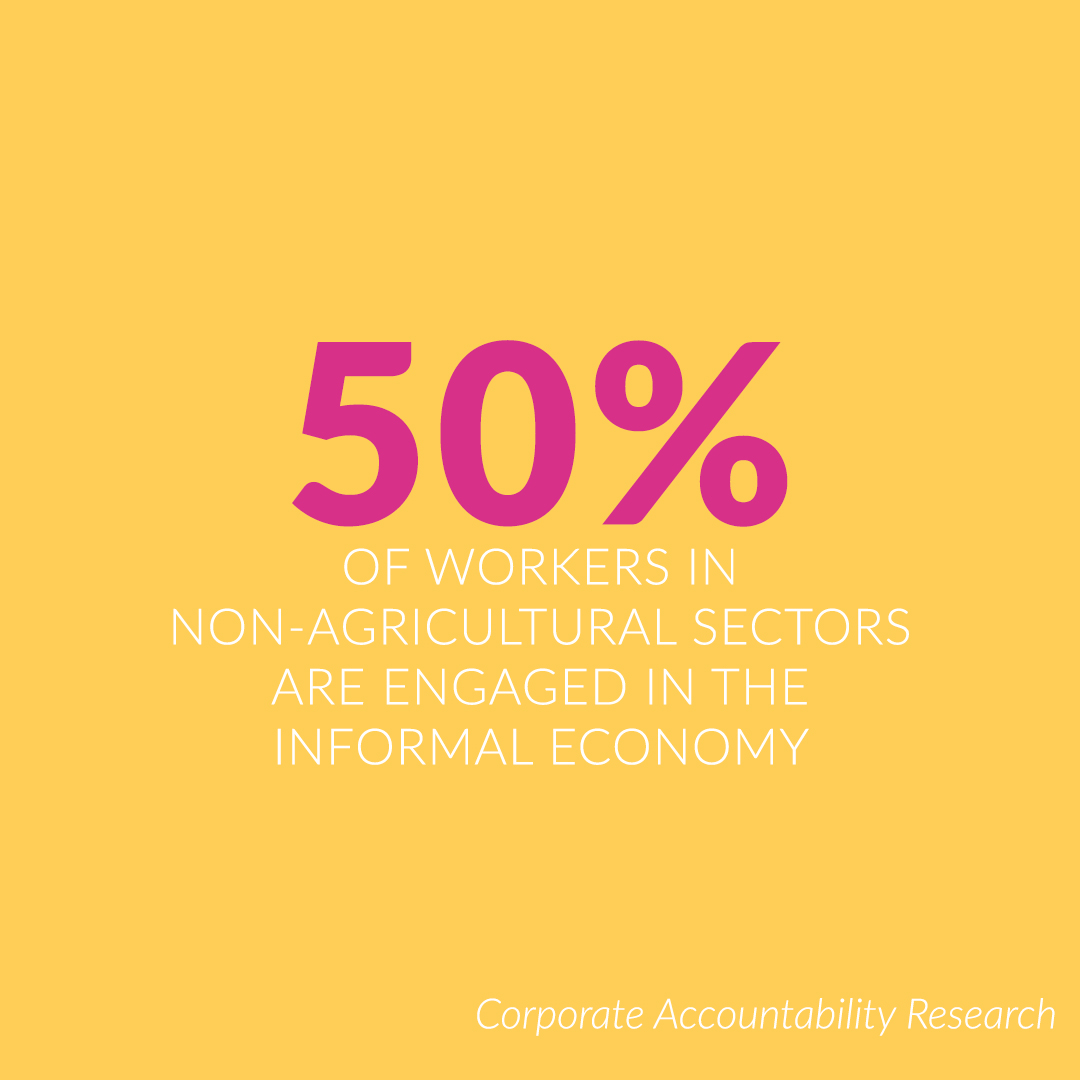

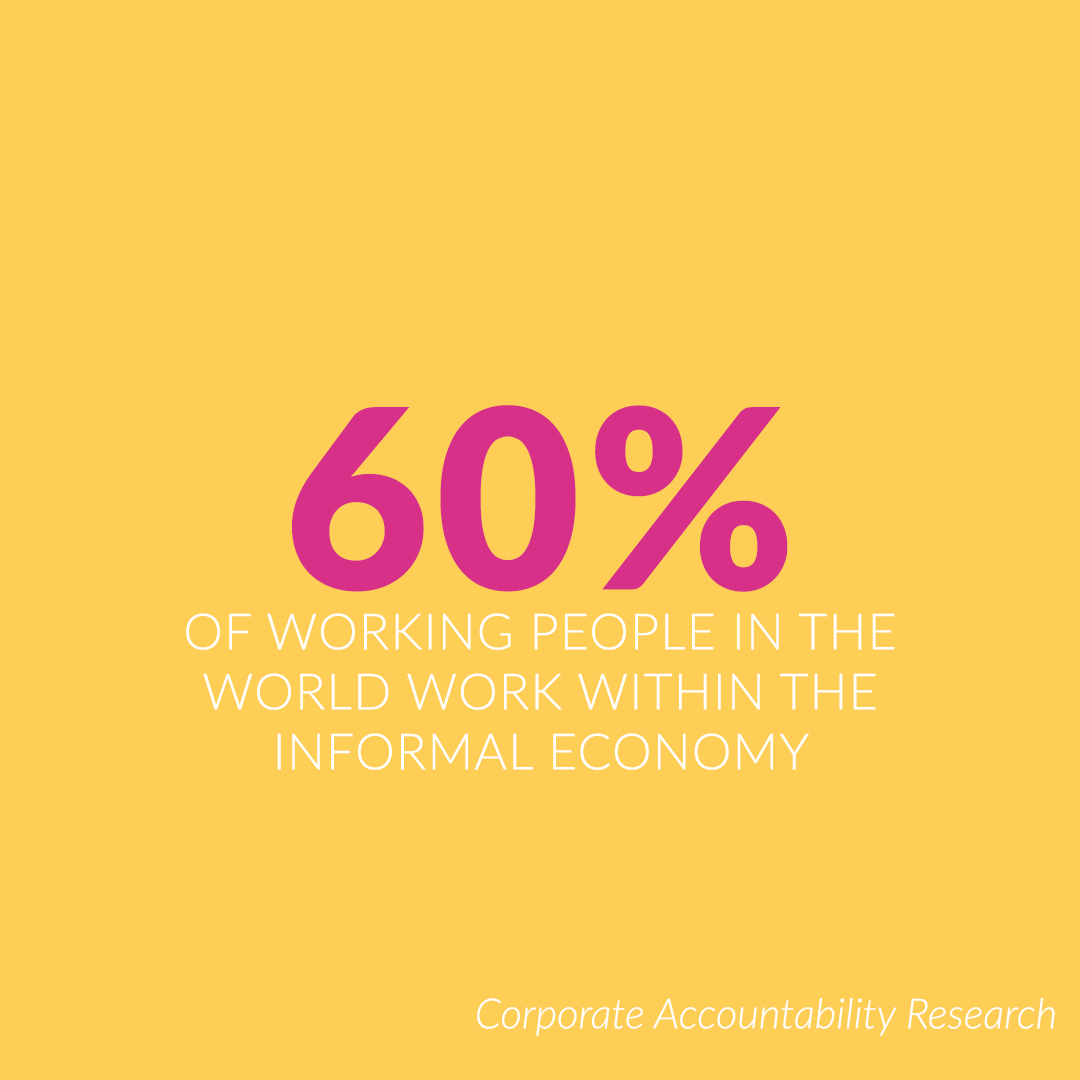

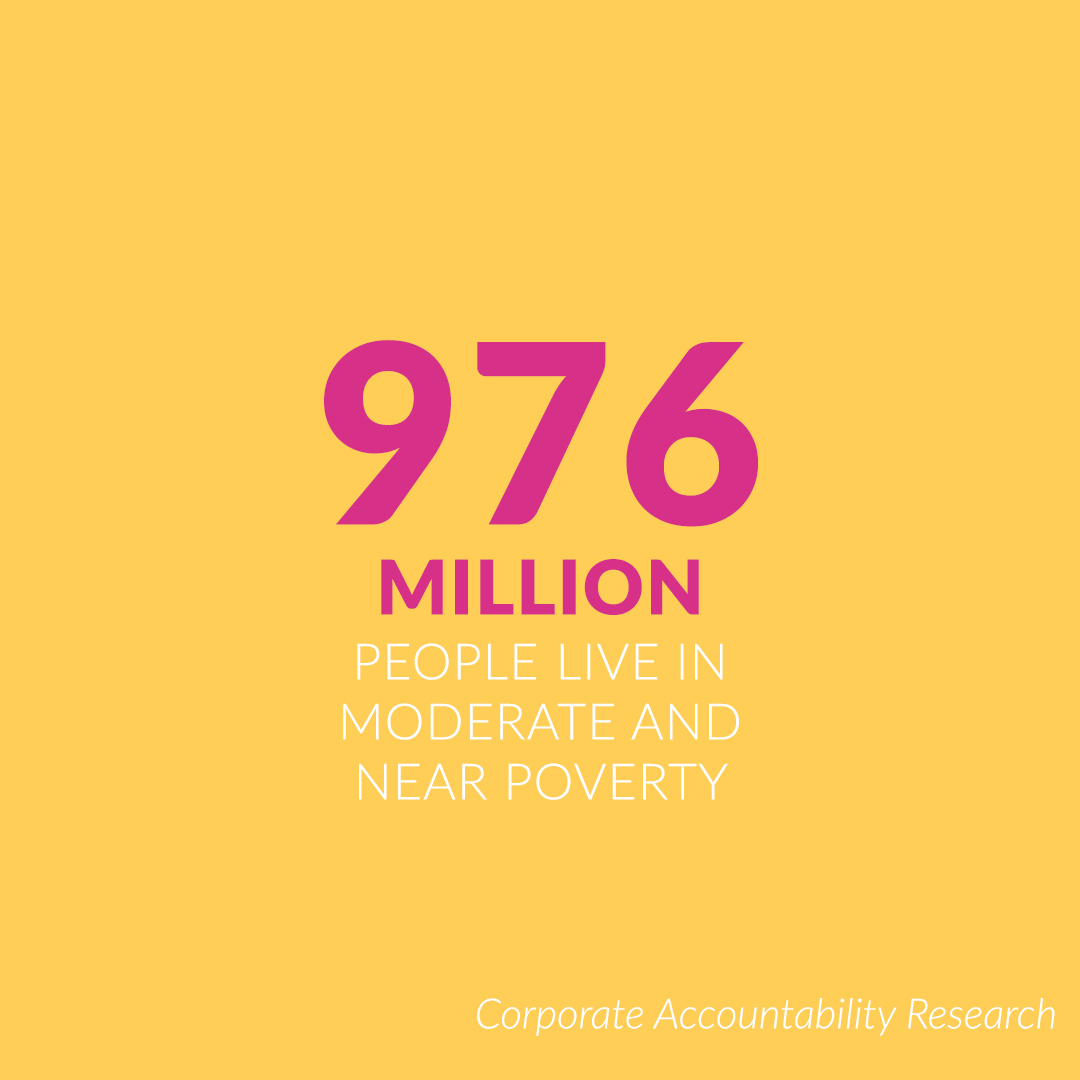

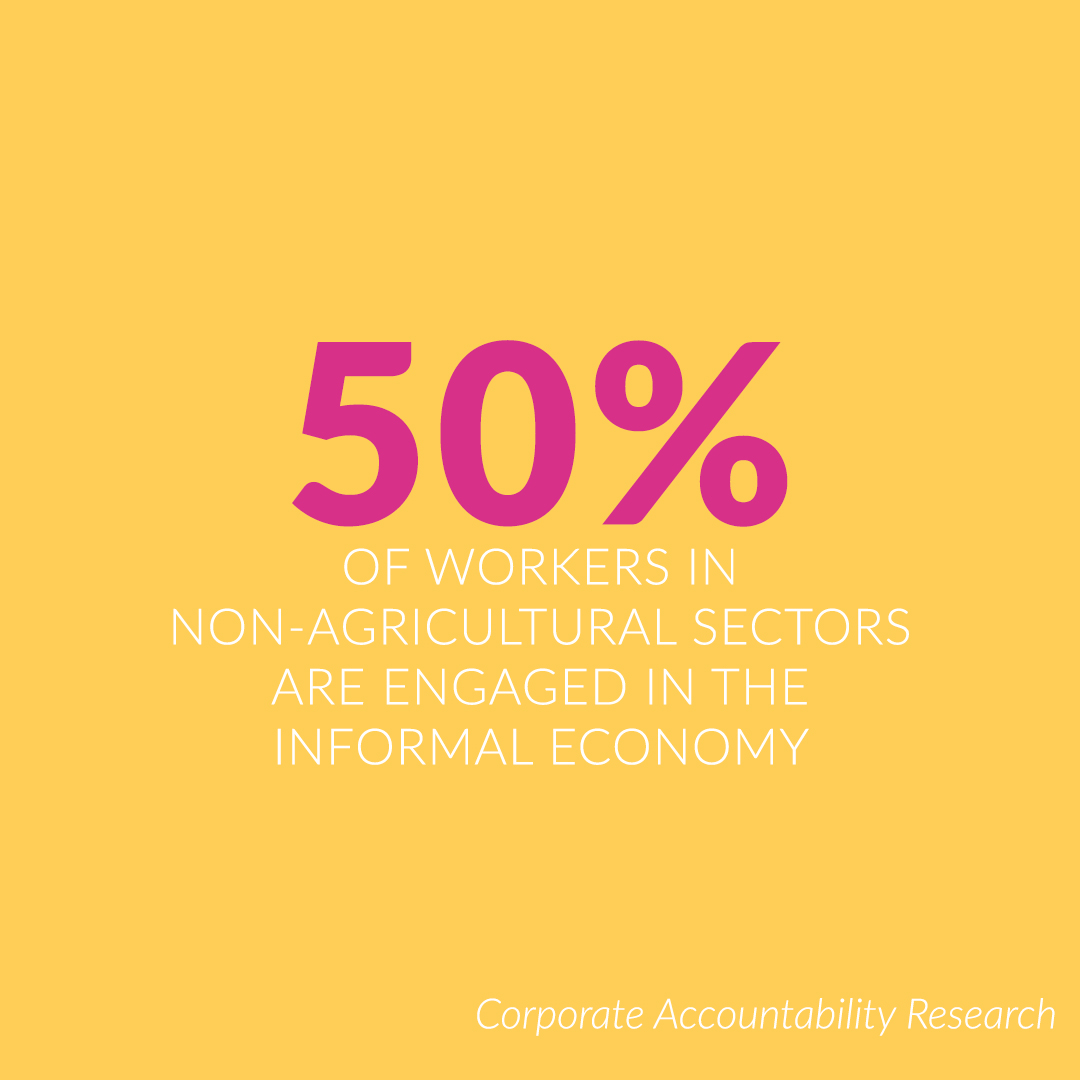

Competition to keep prices low and corporate profits high often results in exploitative labour practices, with the greatest burden on informal and precarious workers. These workers are generally a part of global supply chains, yet, what they earn is not enough to cover basic living costs. Despite efforts worldwide to reduce the number of working people in poverty, progress has stalled. A key reason is that current labour laws are powerless to help these workers as they were designed with a different workforce in mind. Labour laws are national in scope, while work today occurs in global supply chains in which both workers and capital cross borders. Labour laws regulate employment, whereas those pushing down wages often subcontract production. To close this gap between labour laws and today’s mode of production, we need a global living wage backed by an international labour law.

Better Factories Cambodia, the International Labour Organisation and International Finance Corporation's labour inspection body, is coming under increasing pressure from the Cambodian government as part of the pre-election crackdown. My new article explains why.

Government announces some of the details of the Australian Modern Slavery Act.

The case marks an extension of the application of the law of trafficking. "Usually, the conviction for "trafficking in human beings " is linked to procuring or domestic slavery. To my knowledge, this is the first time that the court recognizes in a context of collective work in a company that employees have been subjected to human trafficking" , said Maxime Cessieux, the lawyer of the CGT and employees.

Australia’s only government body charged with hearing complaints of human rights abuses by Australian businesses abroad needs greater support, Kristen Zornada and Shelley Marshall write.

What can the Thai Government do to improve the lives of homeworkers?

How can regulation result in fair wages and ensure human rights in developing countries? Monash Business School's Shelley Marshall explores this issue in her recently-released research. Shelley Marshal is a lecturer and academic at Monash Business School, specialising in labour law, development, corporate governance and accountability at Monash Business School.

It is vital with enforcement mechanisms to ensure that countries work towards a global living wage. One option is to establish tribunals on two levels – international and national. An international tribunal would allow parties representing workers to bring claims against states if they fail to enforce a living minimum wage. National tribunals on the other hand, would have the power to hear disputes between interested parties and corporations. It is suggested that the International Labour Organisation (ILO) would have an orchestrating role for both of the tribunals.